It was September 28th, early evening. I was delighted to find parking on 12th Avenue a few steps from Pacific Theatre and a block away from what I consider ideal window shopping territory – South Granville. Suppressing the urge to head west, I entered Pacific Theatre early. It was an unfamiliar venue, for me, showcasing a new play. The performance I was about to see was A Good Way Out – a Vancouver original, based on a true story.

The stage at Pacific Theatre is flanked by seats on two sides. With clear instructions from friendly staff, I stepped across the stage in close proximity to props carefully frozen in a particular fashion. This brush with unaccustomed territory created the sense of trespassing and it was a relief to step onto the other side and find my place. Being early and seated, I contemplated the set from a comfortable vantage point. A blistering contrast to life on South Granville with its sparkling horizons of promise and eye candy, the set is stark and connotes hard luck and dismal prospects. Thus, before the performance began, my sense of comfort had already been knocked about by minimal, yet telling, settings: a miserable bench seemingly rescued from a defunct car; a motorcycle, presumably once mobile and proud, now standing vulnerable, near a mechanic’s tool chest; and an unadorned, indifferent dining room table and chairs.

I settled in for the play prepared to experience and note how Playwright, Cara Norrish and Director, Anthony F. Ingram tell the complicated and disturbing story of destitution, dysfunction and crime. The lights dim and I’m introduced to Joey, Carl Kennedy, working in an austere bike shop, repairing the motorcycle which is his only way out of a dead-end existence. In the background and clearly audible, Robin Williams portrays the lovable innocent alien, Mork, of the once popular Mork and Mindy sitcom. Mork is telling Orson (see Mork and Mindy – Wikipedia online) about the peculiar way humans deal with loneliness. Meanwhile, Chad Ellis as Sean drifts into the shop, interrupts the program and quickly establishes himself as a shiftless manipulator. He knows nothing of Mork and is not curious. Instead, he engages in a dialogue with Joey that is heavily peppered with salty language, manipulation and aggressive sexual imagery. This juxtaposition of Mork’s scripted sensitivity and Sean’s onslaught of harsh vernacular which is also part of Joey’s reality, is particularly effective in separating the emotional depths of the two characters. It immediately exposes both their differences and commonalities and in this first conversation I am privy to the underlying conflict.

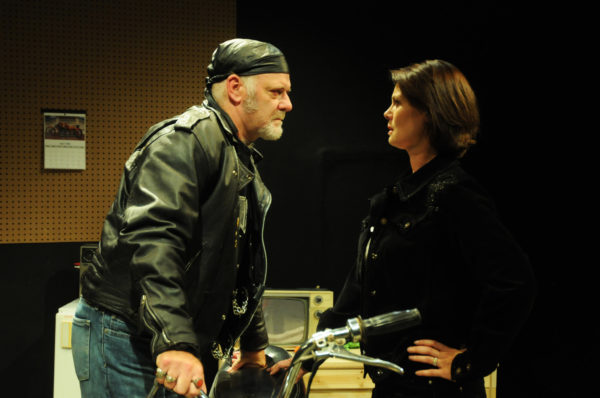

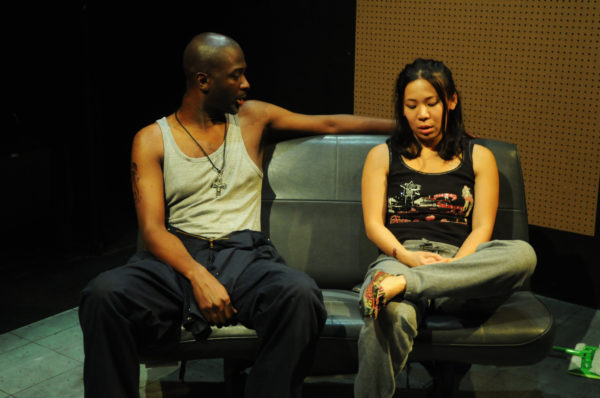

The cast members so skillfully present their character’s individual low ceilings of morality, emotional development and expectations, that I am compelled to step into the claustrophobic world of undesirable choices and jarring consequences. The apt delivery of well-scripted lines and uncompromising scenes convincingly presents behaviour that works for a time in a world dependent on street smarts for survival. However, Norrish makes clear that within this world, as within any world, individuals cannot be captured with a single collective adjective or phrase. This is so with Joey who emerges as a sympathetic character. In spite of his misguided youth and crippling financial situation, he struggles to rise above his environs hoping to create a better place for his family and himself. Kennedy’s portrayal of Joey is strong. His intonation, facial expressions and body language paint the portrait of a troubled, complex man capable of compassion and humour. Kennedy underscores the twisted loyalty Joey feels towards his biker family; while Joey’s partner, Carla, played by Evelyn Chew, exposes the stinging truth of sexual abuse. Chew rises to the challenge of thinking, acting and rationalizing as a partner/mother/nurse with prostitute and stripper stripes. Like Joey, Carla tries to clean up her act in hopes of a better life, but can’t transcend her victim status and is easy prey for cruel antagonist, Larry, brilliantly played by Andrew Wheeler. Both Joey and Carla show the capacity to love and care. Tragically, by the end of the first act it is clear that they are glued to their own destructive loops.

I encourage readers to experience the production and discover the final act for themselves. This is a powerful play about characters embedded in a slice of life most of us are able to avoid. Without visiting the disparate lives of human beings in a compromised world, we cannot fully understand our collective human condition. Norrish tells a timeless story of ill-fated lives not foreign to areas of our own cities. She gives us the opportunity to view and think about social ills occurring within our midst. Most importantly, we are offered the opportunity to see the human side of despair, and to contemplate our role in society’s perpetuation of this travesty.